It was in the summer of 1977 that I first came to Seychelles on vacation from Iran, where my parents had made their home some seventeen years before. I shall not easily forget how, as a city-dweller, its wild beauty first assailed me and then, later, sang to me, as might a siren to a lost traveller, from an island.

Life in Tehran, the capital of Iran, which some still knew as ancient Persia, was pleasant enough and certainly I had no reason then to arrive gasping for contact with Mother Nature as many a city-born traveller does today.

Nestled in the folds of the mighty Elburz Mountains, alternately cooled by the great Russian winter then warmed by the Arabian summer, Tehran was a grand city at the crossroads of civilisation and the Paris of the Middle East.

Already the hub of a mighty empire under Cyrus the Great two thousand five hundred years before, Iran had remained more an empire than a country, containing many different tribes and ethnic groups. A country the size of western Europe, it was a melting pot for Turks, Kurds, Baluchis and Pathans and to which could be added Armenians, Jews, Bahais, Christians and Zoroastrians, those worshippers of fire who predated Islam. As such, it represented a kaleidoscope of cultures, customs, religions, dialects, even whole languages with a topography to match. From the mist-clad mountains and forests of the north to the blistering hot deserts of the south, Iran was as rich in physical contrasts as in ethnic diversity.

Certainly blessed at a cultural level by this rich intertwining of peoples and influences which down through the ages had produced some of the most exquisite architecture on the planet and a plethora of other art-forms besides, each one more refined and accomplished than the next, it was otherwise very much a feudal society ruled by the Shah, or king.

Perhaps one can think of pre-revolutionary Iran as a magnificent stagecoach drawn by a large team of unruly, independently minded horses with the Shah, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, as the coachman. He had the unenviable task of trying to free his oil-rich country of its feudal trappings and manoeuvre it into the twentieth century, running the gauntlet of vested interests both at home and abroad as he did so. Riding shotgun, was the perennial watchdog, Shia Islam, fearful of losing its hegemony over a backward people advancing perhaps too hastily into a modern world, and determined to oppose that advance.

By the end of the seventies there were signs that this stagecoach ride was going to be an increasingly unpleasant one, presaged by rumblings of popular discontent.

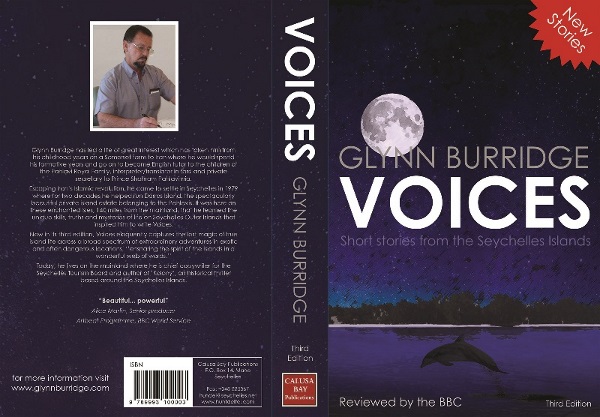

Meanwhile, on vacation in the Seychelles, little did I realise it but the siren had already begun to sing to me. I was on a helter-skelter ride of the senses, awakening to the whisper of surf upon sands of unreal beauty, breakfasting on a rainbow of fruits surrounded by the friendly faces and smiles of a new people. A new world, dramatically different from the one I knew, was beckoning. Borne along in giant pirogues decked out in rich tapestries to sumptuous picnics in remote coves. Swimming with turtles and giant mantas in a living aquarium of crystal waters. Romantic adventures with exotic women whose smooth,perfumed bodies glinted seductively in the moonlight; “moutias” by firelight; spinner dolphins chasing a blood-red sunset. It was a world so enchanting, so unbelievable, I was afraid to blink in case it evaporated.

Inevitably, somewhere along the line, a comparison between the world I knew and the new one whose horizons were spread before me like a banquet, would have to be reconciled and a decision made. But that would come later ; much later. Even then, as the siren sang the eventual outcome was being slowly but surely fashioned by events taking place thousands of miles away, which were spinning giddily out of control.

In September I left the Seychelles to return to an Iran I barely recognised. What had begun as a simple manifestation of popular discontent and confusion had, left unchecked, speedily crystallised into what we know as the Iranian Revolution. The Shah, stricken by cancer, abandoned by his former friends and allies, both at home and abroad, had become an increasingly isolated figure, left to face the wolves alone. Ranged against him was an unholy alliance of radical elements with little or nothing in common except the will to tear apart whatever had been built by him in the name of progress, and what, in all likelihood, will never be built again.

By November, demonstrations in the capital and many of the provincial cities had become the order of the day as the revolution gained momentum. Martial law and curfew were imposed but to little effect as the Shah, essentially benevolent towards his people but misinformed and ill advised by those around him, showed little desire to subjugate the nation by force. The last months before the fall of the Shah were pure mayhem as masses of black-clad supporters of the Ayatollah Khomeini, chief architect of the uprising, spilled into the streets. Working as I did in central Tehran, where I operated as a freelance interpreter/translator in Farsi, but living in Tadjrish, one of its northern districts, with the embattled Royal Family for whom I worked as an English tutor, for me the simple act of going to work became a daily assault course.

Astride my Honda 750, putting my knowledge of Tehran where I had lived since boyhood, to good use, I could avoid many of the roadblocks set up alternately by a crumbling army and Khomeini’s militia. Quite deliberately I kept a few days growth of beard, so popular with the rebels, but which, at an army roadblock could just as easily be passed off as the natural unkemptness of youth. Being bilingual in Farsi and au fait with the customs of the Iranian people I was thus able to ride the twilight zone between the battle-lines. By December it was only a matter of time. Chieftain tanks rumbled ominously in the streets like approaching thunder and it became too dangerous to wander about without good reason.