The Buzzard’s hoard: The fabulous, undiscovered pirate treasure of Seychelles Marbles, a stone horse’s head, a waterlogged woman, a quartz-lined cave and a 300-year old cipher are among mysteries still whispered about on the paradisiacal islands of Seychelles where, it is claimed a fabulous treasure lies buried with a value somewhere in the region of £150,000,000.

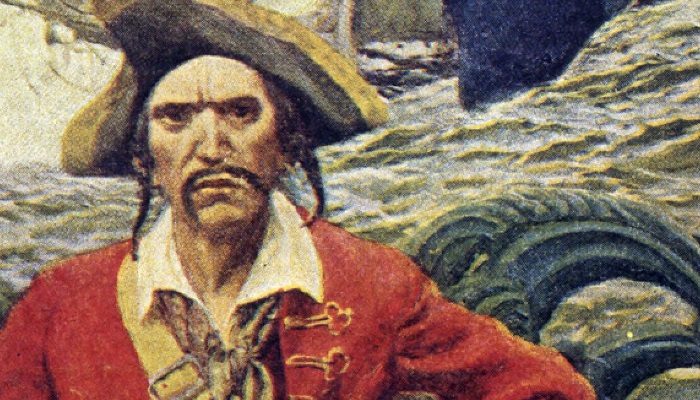

It all began, long ago, with ‘The Buzzard’, a gentleman pirate whose real name was Olivier le Vasseur, born in Calais, France, in the late 1690’s. Also known by the nickname of ‘la bouche’, or ‘the mouth’, Le Vasseur began life on the sea as a corsair in 1716, but then turned pirate and started terrorising the Indian Ocean, taking rich pickings from the lucrative maritime trade routes that criss-crossed that particular part of the world. As was common practice at that time, he teamed up with the English pirate John Taylor and, together, they raided many a merchant ship on the high seas, striking terror into the hearts of mercantile and seafaring communities.

Perhaps it was just the rarest stroke of luck – a massive lottery win in those days before lotteries had even been thought of – when Taylor and La Buse came across the treasure ship, ‘Vierge du Cap’, at anchor, like the proverbial sitting duck, in the harbour of the island today known as La Reunion. At the time, this Portuguese vessel was carrying the Archbishop of Goa and Count d’ Ericiera along with the count’s diamond encrusted sword, church plate, golden goblets, coins, uncut diamonds and – the piece de resistance- a magnificent solid gold cross, seven feet high and encrusted with diamonds, emeralds and rubies, known as the Fiery Cross of Goa.

After the division of spoils, La Buse was left with a problem: most mariners of the time were extremely superstitious about melting down, or otherwise disposing of, religious artefacts. Perhaps it was the sensibility of his crew towards their fabulous hoard that drove the pirates to then do what (it is reported) they then did: conceal the treasure somewhere along the north eastern coast of Mahé, principal island of the Seychelles archipelago.

Seychelles would have been a logical choice because it was out of the way and made up of over a hundred islands among which the pirates could lose themselves and where countless, treacherous reefs would confound any pursuing warships.

Fortunately for the historian, La Buse gets caught up in a piece of history which strongly suggests Seychelles was his choice and, ultimately, his destination. A haunting phrase on a Portuguese map of the period places La Buse at Bel Ombre on the north eastern coast of Mahé with the words: ‘Owner of land…La Buse’. Further adding weight to this hypothesis is that fact that, for a period of several years during the 1720’s, La Buse disappeared from the pirate scene. Was Seychelles his lair during this period of absence? There are those who remain utterly convinced that it was and, furthermore, that, somewhere in the area of what is today Bel Ombre, he concealed his fabulous hoard.

For La Buse, the pirate life came to an end in 1730. In that year he was spotted while working as a ship’s pilot on the island of Madagascar. So casual and carefree was his manner at the time of his arrest that it was even said that he was ‘looking to be caught’. Whatever the circumstances of his capture, La Buse was taken back to La Reunion, the scene of his greatest success, where he was sentenced to a pirate’s fate – death by hanging.

Olivier du Vasseur was taken to the gallows on July 17th 1730 where a fair crowd had assembled to witness the execution of someone who had become something of a household name. Many in the crowd would have been pirates themselves and it may well have been they that he had in mind when he suddenly threw a bundle of parchments skywards with the taunt: ‘find my treasure, who can!’

It seems that several copies were made of these documents, chief among which was what is today known as a pig-pen cipher containing 17 lines of Greek and Hebrew letters. As they gave no clear indication where the treasure was buried, over time interest in the papers would have waned, although copies found their way into various libraries and archives in France, La Reunion and Madagascar, where they slumbered for almost 200 years.

It was not until 1923 that Mrs. Rose Savy, walking her beachfront property in Bel Ombre, Mahé, discovered strange markings on the rocks, unearthed after a particularly ferocious storm. With her curiosity aroused, she then made certain excavations which unearthed skeletons with gold earrings lying nearby. To Mrs Savy, these finds must have whispered the possibility of hidden treasure, innocently beginning a hunt that continues down to this very day.

As chance would have it, a nephew of Mrs Savy just happened to work in archives and, during the course of his duties, had become familiar with the La Buse papers. With these, eventually, in her hands, she must have felt that she was finally getting somewhere but, unable to decipher La Buse’s cryptogram, her quest for the treasure soon hit a dead end.

For some years the papers made the circuit of local adventurers and would-be treasure hunters until they caught the eye of a man who would raise the hunt for the La Buse cache to another level altogether. This was Reginald Cruise Wilkins, ex-Coldstream Guardsman and white hunter who had made his way to Seychelles to convalesce after a bout of malaria he had contracted whilst in Africa. He arrived on the islands in 1947 and, from the moment and laid eyes on the papers, soon after, he was in no doubt whatsoever about their significance.

Having previously worked with ciphers, he was in a good position to begin deciphering the cryptogram and, the very first day he visited the suspected site of the treasure at Bel Ombre, he unearthed two vital clues – the musca, or fly, and the distinctive key hole that someone had chiselled into the flaking granite at the water’s edge. From that moment, Cruise Wilkins was convinced that he had discovered the very place to which the papers referred: the location of La Buse’s treasure.

From the very beginning of his quest, Wilkins found himself in the reverse situation to most treasure hunters: he had, before him, a promising treasure site which he now had to match to a 200-year old set of cryptic clues in order to determine the precise location of the treasure amid huge granite boulders, crevasses and possible subterranean caverns on one side, and steep, densely forested mountainside on the other. He knew that if he could only discern a pattern in the clues and, more importantly, find in them a relevance to the terrain around him, then there could be no doubt that he was on the right track.

Returning to Nairobi to decipher the papers with the help of period French and German dictionaries, Wilkins discovered a possible connection between certain letters and numerals which, in his opinion, denoted bearings and measurements of distance. With the aid of the dictionaries, he also managed to translate some lines of text, one referring to a ‘woman, waterlogged’, another to ‘Jason’. Suspecting that the quest was somehow connected to mythology and astronomy, Wilkins returned to Seychelles where he began excavating in earnest with a team of 23 men. He was greatly encouraged when, after unearthing further signs and symbols, he discovered two letters that corresponded exactly to markings in the cryptogram. However, the biggest breakthrough was yet to come; a flat stone discovered on nearby Mount Simpson upon which detailed compass bearings had been engraved showed that this was the central point in relation to which La Buse’s maps and diagrams must have been charted. A frantic search ensued which proved fruitless until Wilkins realised that the unit of measurement for feet (30.48cm) that he was using, was not the correct one, but rather the old French measurement of 32.4 cm. New calculations led him to the beachfront, to a spot just feet from the high water mark.

Wilkins’s excitement must have reached fever pitch when he found that the retaining wall he was obliged to build there to keep the water and sand at bay while he worked, lay precisely atop another one that someone had constructed earlier for exactly the same purpose! Then, when his downward-digging labourers reached ten feet they struck granite; to be precise, the granite statue of a waterlogged-woman. Andromeda!

Months of excavation around the statue unearthed layers of lime cement, (commonly used by pirates, and made by burning coral until it turns to lime), but also etchings of a scimitar blade next to a ram’s horn and the chiselled form of a ship which Wilkins called ‘Argo’ – Jason’s ship. Slowly but surely, a pattern was emerging in which every fresh clue was finding its rightful place.

Rummaging further through the hillside opposite, Wilkins came across further clues; a stone representation of Pegasus, Perseus’ winged horse, beneath which lay a cavern fashioned with clay and fragments of quartz. Was this the treasure cave that La Buse built but never used? Not far off, was a rock bearing hoof print-like markings which Wilkins recognised from his hunting days as those of a stag and which would prove to be another major find.

Wikins, who had long wrestled with the what he believed was the underlying theme to the clues La Buse had laid, now began to see their undoubted connection to Greek mythology and to the Labours of Hercules – one of Jason’s companions – which he had to complete in order to achieve immortality. One such labour was the capture of the Ceryneian stag. Over a period of some five years, he began to unearth representations of other labours, each time accompanied by the same three circles cut into the rock face and echoing another deciphered line from the papers; ‘Let Jason be your guide and the third circle will be open unto you’.

Markings of a boar’s footprints and unearthed cattle bones pointed the way forward, each time accompanied by letters identical to those in the cryptogram, which threaded a path to further clues spread over an area of some 70 acres. On the way, Wilkins’s quest unearthed much in the way of artefacts that could only have served to strengthen his conviction that he was, indeed, on course to find the treasure; porcelain statuettes, an oil jar, the statue of a ram, a headless shepherdess, a flintlock pistol and a fine collection of white marbles.

A lack of funds forced Wilkins to return to Nairobi to look for sponsors to purchase shares in the treasure that allowed him to buy new equipment and return, but only to meet with a fresh obstacle in the form of a Public Works Department concerned at the dig’s effect on the condition of the road through Bel Ombre.

Still, the procession of clues led Wilkins onwards, past a representation of a bull’s horns and an etching of what Wilkins took to be the Golden Apples of the Hespiredes to the carving of a dog which, for Wilkins, indicated Hercules’ very last labour – the capture of Cerberus from the Underworld.

In all this time, Wilkins search had led him full circle; from the Bel Ombre beachfront, up the adjacent hillside and back again to the Ocean’s edge, but still the treasure eluded him. Now, the underworld connection and the topography of the site itself suggested to Wilkins that La Buse may well have found a natural underground cavern in which he had hidden his treasure and then blocked its entrance with giant boulders. All he needed was heavy equipment to bore his way through to it.

By then, Time and Lady Luck were not on Wilkins’s side. Everywhere around him were tantalising clues that the treasure was, finally within reach: a small boy lowered down a passage between the boulders came up covered in rust; the reading from a proton magnetometer suggested 35 lbs of metal lying at a depth of 18 feet and a plan for the construction of Seychelles’ new international airport was bringing into the country precisely the type of heavy equipment that Wilkins needed to complete the task.

On the other hand, funds from investors was fast drying up as was the enthusiasm of the local work force. Wilkins’s health was also failing and Costain’s, the company contracted to build the airport, announced that were not able to make the heavy equipment Wilkins needed, available to him.

Reginald Cruise Wilkins dedicated much of his life to a battle of wits with an 18th century pirate and sacrificed his savings – and his health – to the rigours of a dig lasting 27 years which, he believed, had brought him within feet of final victory. Sadly, that victory was not to be his and, at his death in 1977, he passed the treasure hunter’s baton to his son, John.

Today, John Cruise Wilkins is gearing himself up for the task ahead. A great optimist and believer in the presence of the treasure, John has undertaken painstaking research that has led him, in his mind, to a particular part of the site at Bel Ombre. As he approaches the Government for a fresh licence to excavate and dreams of sharing the mysteries and wonders of the quest (and the enormous historical and architectural significance of the site itself) with a tourism development of the location that will run parallel to future excavations, he too, it would seem, hearkens to that ancient voice still whispering its timeless challenge from somewhere among the granite boulders of northern Mahé:

‘find my treasure, who can!’